This is a guest post on slow clothing by author and textile collector Sheri Brautigam.

The concept of slow clothing – hand-made artisan clothing – has been a reality for most of the world until very recently. Commercial goods either weren’t available or too expensive for people in developing countries to buy, so making your own garments from cloth you had woven, or even further back, animal skin you had scraped and cured was the norm.

Has it become a buzz word now because we have become aware of the realities of sweat shops in Asia, employing mostly women, who work long hours under wretched conditions to be paid very little per piece they construct? All this so we can buy a dress for $19.99? Our American culture has the luxury of asking these questions because we have options. But the real question is: Are we willing to pay a fair wage to someone to construct our clothing and are we willing to wear it day in and day out like most of the world?

Either it was pure luck or my destiny to end up in an area of central Mexico with spectacularly dressed Mazahua indigenous women, who appeared at the market and on special religious holiday occasions. After several such encounters I decided to find out who they were and found my way out to their little town. Unbeknownst to me, I was about to experience ‘REAL slow clothing’. Were these brightly dyed handwoven embroidered garments for sale? I was told they were very difficult to make and probably weren’t for sale, but there was a revival project going on to teach some of the techniques necessary to make the elaborate and heavy costume.

This visit turned into a several month documentation of a very old ‘traje’/costume made of hand spun wool, which was then dyed with natural indigo, cochineal, and wild marigolds. The skirt length was easily 3 yards long, woven on a back-strap loom and weighed close to 15 lbs. The top was a small poncho type caplet called a ‘quechquemitl’ – very unique to central Mexico but with antecedents way back to pre-Columbian times. The Mazahua ladies were on the verge of losing the skills necessary to make these ‘trajes’ which are an important part of their cultural identity but worn now mainly for their ceremonies and festivals.

The story goes, that a young Mazahua girl, in order to take her place in the community as a woman/adult, needed to hand-spin the wool for her traditional ‘traje’. This probably took a bit of time as the two pieces weigh close to 15 lbs. She didn’t necessarily need to know how to weave but needed to promise something in return ‘treque’ /exchange- some thing she could do or had, perhaps (chickens?) to trade the woman weaver. Then it needed to be sewn together and embroidered on the edges. Perhaps her grandmother did that for her. After all it was 18 feet and had to be finished at each end. A ‘traje’ went through ‘mucho manos’/many hands and usually took at least a year to make.

Today very few young girls are drawn to learning the skills to make this costume, so they borrow their relatives older pieces for the fiestas. Sadly there is acrylic knock-off material that mimics the fine stripes and colors of the heavier hand woven skirts. It’s now popular and the go-to material if you need a skirt as they are so much lighter to wear and so affordable.

Will REALLY slow clothing survive in this Mexican Mazahua village? There will be a semblance of the highly complex and laborious costume because after all this is how they identify themselves and their community from other Mazahua.

A years worth of labor passing through many hands to make one spectacular costume!

REALLY slow clothing. Would you be willing to pay to have them made?

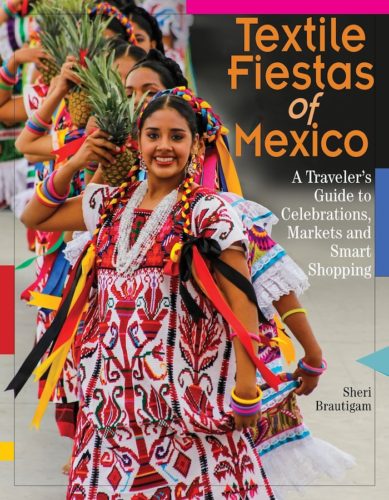

Sheri Brautigam is a collector, and documenter of traditional textiles of Mexico. She was training Mexican English teachers when she first started following her textile passion and visiting many famous Fiestas, artisan fairs and markets all over Mexico.

She has just published: “Textile Fiestas of Mexico – a travelers guide to Celebrations, Markets and Smart Shopping” – THRUMS – available on Amazon.

She has just published: “Textile Fiestas of Mexico – a travelers guide to Celebrations, Markets and Smart Shopping” – THRUMS – available on Amazon.

Visit her blog to learn more about slow clothes and Mexican Textiles:

http://livingtextilesofmexico.wordpress.com

Etsy Shop for collector textiles: