by Ansie van der Walt

Image above: a Ramallah (Palestine) head shawl, photo from @tirazcentre

In her book Threads of Identity, Widad Kawar tells the stories of four women she knew who played a significant role in not only creating beautiful tahriry embroidery and malak outfits but in spreading its legacy across Palestine and beyond. Women from Beit Dajan and villages in the Jaffa area were fond of a style introduced by Manneh Hazboun, who added Bethlehem couching to pieces already decorated with the local cross-stitch designs. Her designs became so popular that she started her own business.

“She would take the Beit Dajan embroidery pieces to Bethlehem to be embellished by Jamila Hazboun Mahyub, or at the workshops run by the Hazbouns. At first, the work added in Bethlehem consisted only of rose branches on the skirt, but then some wanted it on the chest panel too. Later on, Manneh’s mother and brother helped her start a workshop where she taught Beit Dajan girls Bethlehem style embroidery, including new connecting stitches, couching, and applique.”

Threads of Identity – Preserving Palestinian Costume and Heritage by Widad Kamel Kawar, p.158

Jamila Hazboun Mahyub, a full-time embroiderer with a career spanning forty years (1915-1945), had an embroidery workshop in Bethlehem employing forty women and girls. She specialised in creating bridal trousseau. Her work was so famous that women came from as far away as Ramallah to obtain Bethlehem-embroidered sleeves to add to their dresses. She often created new designs, and many of the now popular designs with names such as raisins, sugar cubes, nuts, and apple blossoms were invented by her.

After the war in 1948 Jamila’s business steadily declined as people disappeared into refugee camps, and she closed her shop in 1956. Jamila gave her last remaining embroidery samples showing the steps for making a pattern, her wooden spool with silk threads, and a photo of herself to Widad Kawar on one of her last visits. “They are for your museum.”

Introduction to Arab Embroidery

This peek into the lives of Palestinian women during the first half of the 20th century reveals how the simple act of embroidery permeated every layer of society and how textiles, handcraft, and dress influenced and shaped history and heritage in the Middle East and around the world.

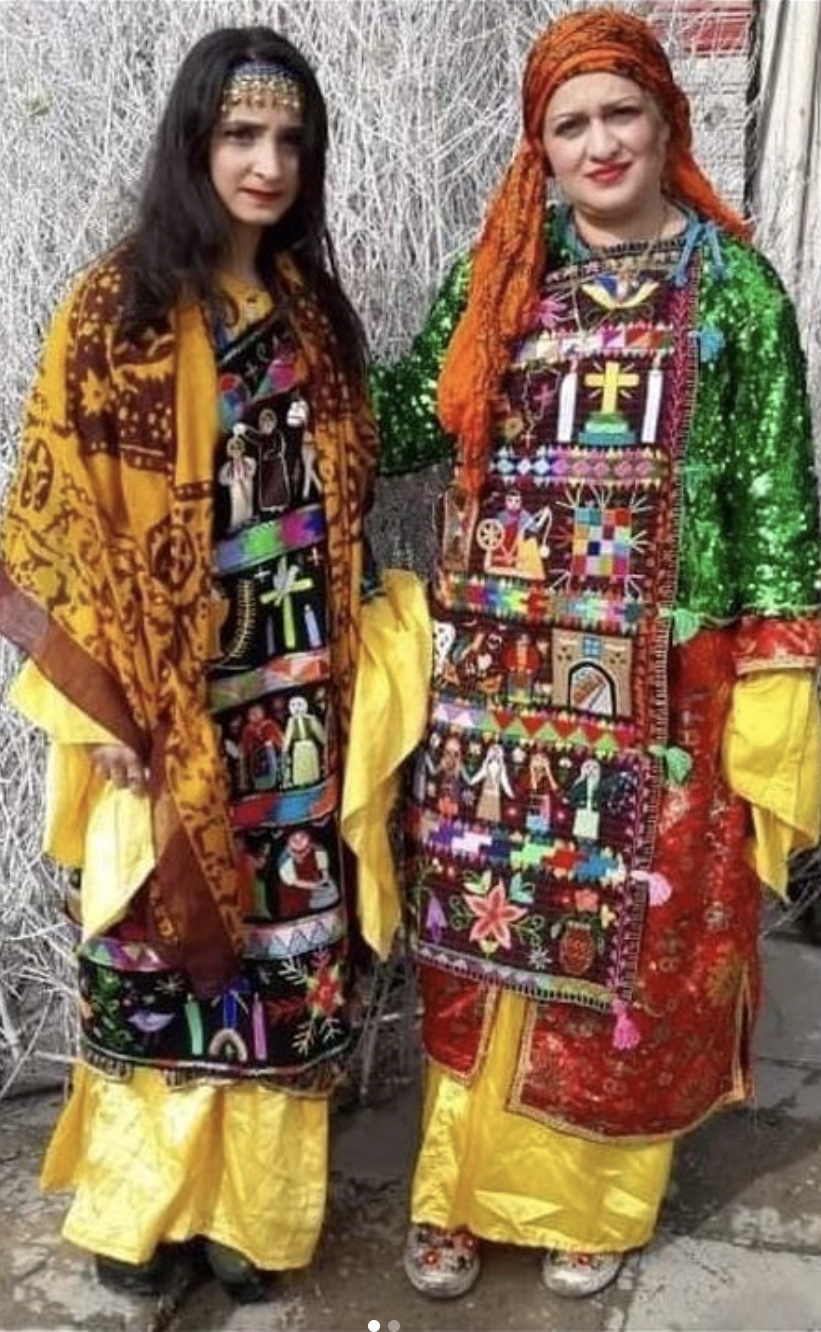

Contrary to what many people outside the Middle East believe, and the images they see of women covered from head to toe in black, Arab women love to adorn themselves with colour and embellishments. Every piece of cloth, bead, stitch, and thread tells a story, identifies a person, tribe, or region, celebrates an occasion, or signifies a social standing.

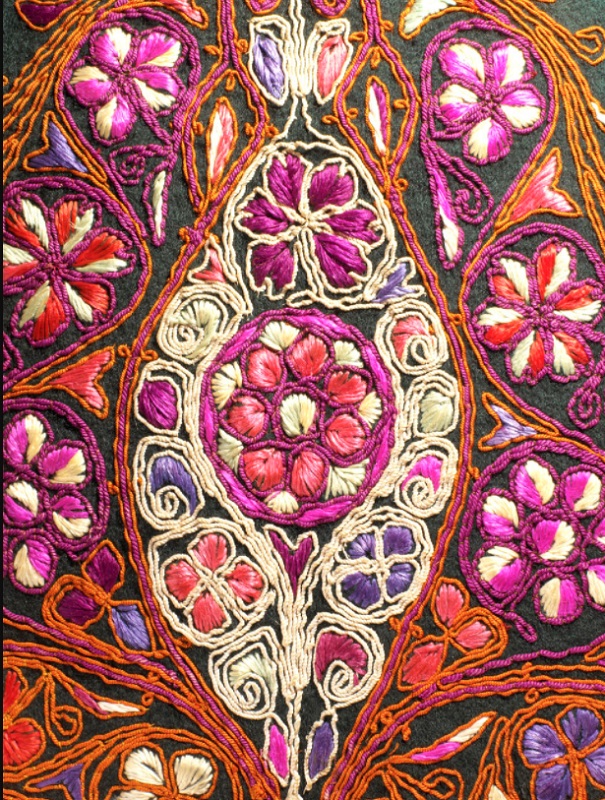

The earliest known embroideries from the Arab world were found in the tomb of the Egyptian Pharaoh Tutankhamun who died in 1323 BCE. Embroidery has been part of the culture and history of the region to the current day. The term Arab embroidery often envisions geometric and floral designs created in cross-stitch (also known as Palestinian embroidery or Tatreez), yet the region and its different cultural and religious groups are home to a much wider and richer stitched legacy.

Embroidery as identity

Embroidery patterns are seldom mere decoration. Motifs have meaning. Some are designed to ward off evil or protect against the evil eye, others are meant to indicate social status, rank, or even vocations, while others depict organic patterns representing local produce, fauna, and flora, as well as arabesque or calligraphy designs. Strangers on the street or in the marketplace could often be identified or recognised as from a certain area or village by looking at small variations in embroidery patterns, colours and designs. As Widad Kawar explained, women from one village might adopt designs from another village but then add their own distinct improvements or adaptations, creating a new identity.

In her book Reveal and Conceal – Dress in Contemporary Egypt, anthropologist Dr. Andrea Rugh explains how she was conducting other anthropological research in the lower-class urban quarter of Cairo that attracted migrants from rural areas all over Egypt when she noticed how the local women were able to glean a considerable amount of information about strangers based on the way they were dressed. This intrigued her and she set out to systematically trace the patterns of dress throughout Egypt, “unwinding in effect, the tangled web of costumes from the Cairo quarter, back to the single strands of their beginnings.”

Embroidery as women’s work

Although many artisan crafts, such as silversmithing, were mainly done by men as a vocation, embroidery is almost exclusively a women’s pursuit. Although there were women who stitched for an income or as a vocation, as with Jamila Hazboun Mahyub mentioned above, embroidery was women’s work. Girls learned from their mothers and grandmothers, they honed their skills and worked on creating their trousseaus, including clothes for all occasions, household items, and decorations for a future home.

“The world of women’s craft is a fascinating yet hidden one, where most women work in discreet intimacy. Embroideries, however, provide us with the perfect gateway into their minds and lives. Behind every piece of embroidery are the efforts, the tears, the laughter, and the ambitions of the woman who created it. It is thus a very intimate world that is shy to reveal itself, as embroideries are the demonstrations and living testimony of what many women do in their secluded domestic world.”

Isabelle Denamur – A Story of Islamic Embroidery in Nomadic and Urban Traditions

Embroidery as a trade and travel record

The Middle East and Arab world are at the crossroad of major trade routes between East and West, between Europe, Asia, and Africa. It includes a significant part of the Silk Road and has been the home base of renowned travelers and traders throughout history. Shipping routes, caravan routes, and, in modern-day, flight paths cross here. Cloths such as cotton and silk, as well as beads and threads have been used as both a currency and a commodity throughout history. These articles of trade found their way into the local dress lexicon either by incorporating the fabrics, beads and threads into the local fashion or by adopting and adapting foreign patterns and motifs into local embroidery designs.

Keeping traditions alive

History and tradition are not static. They are alive and changing all the time. Empires and ruling powers come and go; political borders and affiliation change; environmental, agricultural, and natural resources blossom and diminish; technology and industry create new inventions and bring others to an end. It is the circle of life.

The Arab world has seen more than its fair share of all these things. Politics, religion, and the discovery of oil have brought major changes to the region over the past few generations. Many of the customs, crafts, textiles, and way of dress inherent to the region do not exist anymore or are fast disappearing.

As the current generation of custodians, we have a responsibility to document and preserve these customs and traditions, and we do it by:

- Passing knowledge on to the next generation, especially those in the diaspora;

- Recording the stories of our mothers and grandmothers;

- Preserving historical dress and adornments in archives, museums, collections, and galleries;

- Keeping traditions alive by reinventing them, adapting them to contemporary needs, and making them viable in modern society.

Those of us outside the Arab culture but with an understanding and appreciation of craft, textiles, and cultural heritage, can support one of the many institutions that are dedicated to keeping the heritage alive.

- Tiraz Centre, founded by Widad Kawar. The home of Palestinian and Syrian dress. Based in Amman, Jordan.

- The Zay Initiative, founded by Dr Reem el Mutwalli. Working to preserve and archive Arab dress heritage. Registered in the UK and based online.

- Mansoojat Foundation, an online museum and archive of Saudi Arabian dress heritage.

- Textile Research Centre, founded by Dr Gillian Vogelsang Eastwood. Based in Leiden, The Netherlands.

Further Reading

- Moroccan Textile Embroidery, Isabelle Denamur, Flammarion, Paris, 2003 – The benchmark of Moroccan embroidery books. Available in English and French. See a review here.

- Encyclopedia of Embroidery from the Arab World, Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood, Bloomsbury. Find a review here.

- Traditional Costumes of Saudi Arabia – The Mansoojat Foundation Collection, 2021

- Reveal and Conceal – Dress in Contemporary Egypt, Dr Andrea Rugh, 1989

- Threads of Identity, Widad Kamel Kawar,

- A Story of Islamic Embroidery in Nomadic and Urban Traditions, Isabelle Denamur, TDIC, Abu Dhabi, 2010 – This book was published as an exhibition catalogue but contains a wealth of information and excellent images. It is hard to find but a real gem and well worth the effort and money.

- Textiles of the Islamic World, John Gillow, Thames & Hudson, London, 2010

- Embroidered Textiles, Sheila Paine, Thames & Hudson, London, 2008.

- Traditional Women’s Dress of Oman, Julia M. Stehlin-Alzadjali, 2010

Ansie is a South African-Australian textile writer based in Dubai. She specializes in writing about cultural textiles and textiles in fine art. She regularly contributes to a range of textile and needlecraft publications including Inspirations Magazine, Garland Magazine, and Textile Fibre Forum Magazine, and she contributes to The Zay Initiative by serving as their Content Manager. On her own online platform, The Fabric Thread, she focuses on cultural textiles in the context of travel, books, and art.

She follows the threads and finds the stories, using them to spin new yarns and weaving new fabrics – of people, places, and cultures. Her motto is Talking Textiles, Crafting Community, Stitching Stories.