by Deborah Chandler and Todd Jailer

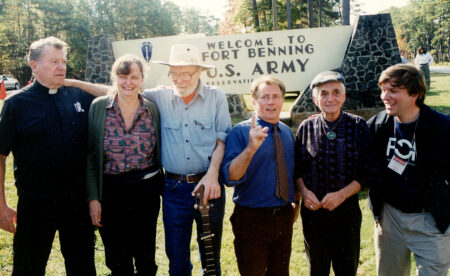

Image Above: San Carlos Foundation founders and friends at the School of the Americas Watch protests.

From left to right, Father Bill O’Donnell, Dr. Davida Coady, Pete Seeger, Martin Sheen, Father Daniel Berrigan, Father John Dear.

Many WARP members have an idea of what the Peace Corps is about; in fact many WARP members have been Peace Corps Volunteers. At the moment the Peace Corps is on hold, all volunteers having been brought home due to the COVID Pandemic. While all PCVs have a strong desire to serve people internationally, not everyone wants to do their service connected to the US government. So what if you want to do that service but the Peace Corps won’t work for you? Are there alternatives? Yes, there are, and this story about the San Carlos Foundation describes one of them.

In 1984, most international volunteer-sending organizations were not placing people in Central America because of the ongoing wars in the region. To Dr. Davida Coady, who spent much of her career providing care in refugee camps on almost every continent, that made no sense: war zones, refugee camps, urban slums and remote rural villages are often the places where skills, support, and solidarity are needed the most! So together with Fr. Bill O’Donnell, a veteran of United Farm Workers organizing in California, and the actor and activist Martin Sheen, they founded the San Carlos Foundation, based in Berkeley, California. While San Carlos can’t compete with the Peace Corps in numbers of volunteers – they have funded about 150 volunteers in almost 40 years — they are a small organization with a large footprint.

On a trip to Guatemala in the 1980s, Martin Sheen, Fr. Bill O’Donnell, Dr. Davida Coady, and Guatemalan Fr. Andres Girón.

Their idea was to fund work by people that was otherwise “unfundable.” Over the years, volunteers have:

- taught photography to children who live in the Guatemala City dump;

- provided health care in conflict zones;

- documented human rights abuses and trained human rights workers;

- helped cooperatives develop accounting skills;

- trained communicators in journalism and community radio;

- and shared skills from welding to desktop publishing to latrine-building to small hydroelectric generation. (See a short report on the last of those at the end of this story.)

While San Carlos volunteers have helped various artisan groups develop marketing plans, so far they have had no weavers as volunteers!

Their website explains:

We provide health and educational assistance to refugees and other people living in extreme poverty in the developing world, particularly in Central America. We grant minimal living expenses—currently $6,000 a year—to doctors, nurses, lawyers, engineers, teachers and other professionals who volunteer their time, live in primitive conditions and train local people to continue their work when they leave.

Although San Carlos asks for a one-year minimum commitment, many volunteers stay much longer. Local language skills and previous third world experience are prerequisites, as are skills useful to the population with whom the volunteer intends to work. Unlike the Peace Corps, volunteers do not go in blind to a situation arranged for them; instead, volunteers need to know where they are going and why, and have a pre-arranged agreement.

Over the past few years the number of young people who have studied international development work at the university level and are now embarking on careers in the field has grown tremendously. It is very exciting, as it brings a whole new energy and mind-set to the work. No longer dedicated to one project for life, these young activists are dedicated to the concepts of fair trade, justice, supporting local efforts, and so much more, and finding myriad ways to go about it. Many WARP members are involved in such endeavors, and for those who are interested in working in the field and gaining valuable experience as well as providing real help, the San Carlos Foundation might be able to help them reach that goal. At the same time, for those who are passionate about the idea and the need but cannot go into the field themselves, supporting this foundation is an option. Well worth knowing about, their methods and goals are totally in alignment with WARP’s mission and goals.

You can find out more or contribute to the San Carlos Foundation on their website: www.sancarlosfoundation.org or by writing to Todd Jailer, President and himself a former volunteer: .

How to organize and install a micro-hydroelectric plant

from a report to the San Carlos Foundation from Rebecca Leaf and ATDER-BL

(Asociación de Trabajadores de Desarrollo Rural – Benjamín Linder)

These projects start with a rural community like this one, Valle Los Condegas:

After checking out a nearby stream, the first step is a series of community meetings to discuss the possible construction of a micro-hydroelectric system and to form the community committee for this project.

The second step is the preparation of the design and budget for the project (ATDER-BL does this work usually on a volunteer basis). Then the search for financing for construction begins. When funding is secured, so does the physical labor. Here a village volunteer work brigade starts building the water intake:

The water intake is a very small dam that diverts some water from the stream into a plastic pipe.

Then pipe is installed from the dam to the powerhouse. The powerhouse is the small red building (see photo on other side) that protects the turbine and generator. Next to the powerhouse, the first post of the electric grid is installed. Depending on the distance to be covered by the electric grid, a transformer may be needed on the first post.

We build these small water turbines at our metalworking shop in the town of El Cua. Bringing the turbine into the powerhouse is difficult, but anything is possible if you have enough people working together.

Then we connect the turbine to the water pipe that brings the water down from the dam. The pulleys and belts that transfer the water’s energy from the turbine to the small electric generator are installed. Then we put up the posts and string the cables of the electric grid.

Finally, we test the lights in the houses, school, hook up the refrigerators, public telephones, etc. With electricity, the community feels different both by day and by night. The people gather to celebrate with prayers and blessings, speeches and poems. The inauguration lasts all afternoon with music, dancing, lots of food, and piñatas for the children.

This small rural electrification project benefits 100 families.

It is difficult to express the depth of the gratitude I feel towards the San Carlos Foundation for the support you have provided me during the years of war, and continued during the years of peace. Without your support, none of this work would have been possible.